3 Planning

Being able to decide where to go paddling and being able to plan a safe day on the water are the most important things that we’ll cover on the course. We’ll cover the basic theory and spend time applying it to hypothetical situations before using our planning skills on trips.

Please do get involved with trip planning as much as you can. Get hold of guidebooks and maps for the locations that we’re heading to (I’ll have a few copies to share). Spend some time on the Friday night car journey getting weather forecasts on your phone, coming up with ideas and discussing them with the people you’re travelling with. We’ll start each day with a group discussion of our plans. The more you’ve thought about this ahead of time, the more you’ll get from these discussions - which are probably going to be the most valuable learning opportunities on the course.

3.1 Wind forecasts

The weather, especially the wind, is critically important to sea kayakers.

The main things to know about the weather are where to find a good forecast and how to interpret it.

Unsurprisingly, the internet is a great source of weather information. Good sites include:

- https://www.metoffice.gov.uk - the ‘official’ forecasts for the UK, including marine forecasts

- https://www.windy.com - my current favorite site

- https://www.windfinder.com - usable interface and a good phone app

These forecasts will give the following information:

- Wind speed

- Wind direction - typically given as the direction that the wind will blow from. However, many forecasts will provide an arrow in the direction that the wind is blowing to. Useful to know, as we can plan paddles that start by going upwind to give us an easy homeward leg, or we can choose to find shelter behind the land (but beware the dangers of an offshore wind).

- Information on waves

- General weather - cloud, precipitation, temperature - how miserable or pleasant will the day be? How much of a danger is hypothermia if things go wrong?

It is useful to be able to interpret the inshore waters forecast issued by the met office. This is available:

- on the Met office website

- on Radio 4

- over VHF radio at regular intervals

The forecast includes the following elements, in order:

- Wind strength (Beaufort scale) and direction -e.g. “West 4 or 5, backing southwest 5 or 6 later.”

- Sea state - e.g. “Slight or moderate.” See below.

- Weather - e.g. “Occasional rain later.”

- Visibility - e.g. “Good.”

Some of the terms used in the forecast are explained in more detail below.

Timing - the words used have precise meanings:

- Imminent: within 6 hours

- Soon: 6-12 hours

- Later: >12 hours

Sea state - innocuous sounding sea states can cause problems for kayakers:

- Calm: <0.1 m wave height

- Smooth: 0.1-0.5 m

- Slight: 0.5-1.25 m

- Moderate: 1.25-2.5m

- Rough: 2.5-4m

Visibility

- Good: > 5 miles

- Moderate: 2-5 miles

- Poor: 1 km to 2 miles

- Fog: < 1 km

The map shows the places referenced to define the areas of the forecast.

You hear the following over your VHF:

‘The inshore waters forecast, issued by the Met Office at 05:00 UTC on Tuesday 2 June 2017 for the period 06:00 Tuesday 2 June to 06:00 Wednesday 3 June. St Davids Head to Great Orme Head, including St Georges Channel. 24 hour forecast: West 3 or 4, backing southwest 6 or 7, later. Smooth, becoming moderate later. Rain later in north. Good, occasionally moderate later.’

How does this affect your paddling plans on Anglesey?

The weather for today’s paddle seems reasonable for a competent group, but we might choose to start the day paddling westwards into the wind so we can be blown home. We expect less than 0.5 m waves. Visibility should be at least 5 miles.

The weather ‘later’ - i.e. after 18:00 UTC or 19:00 British Summer Time sounds decidedly worse, but we’ll be off the water by then. The wind overnight would make paddling difficult, as would the waves up to 2.5 m. We’d expect rain, which will limit visibility to 2-5 miles.

3.2 Impact of wind

It is important to be able to understand the effect that the wind will have on us as sea kayakers. The table below describes conditions at each level of the Beaufort Scale, along with wind speeds in other units.

| Beaufort force | Speed in knots | Speed in mph | Sea conditions | Land conditions | Paddling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-3 | 1-3 | Small ripples | Smoke drifts, but wind vanes don’t move | Easy |

| 2 | 4-6 | 4-7 | Small wavelets that don’t break | Wind felt on face, leaves rustle and wind vanes move | Easy |

| 3 | 7-10 | 8-12 | Large wavelets, which occasionally break | Leaves and twigs in motion, light flags extend | Fairly easy, but noticeable work paddling into headwind. Novices struggle in crosswind. |

| 4 | 11-16 | 13-18 | Small waves, frequent white horses | Raises dust, small branches move | Effort into headwind. Following seas start to form. |

| 5 | 17-21 | 19-24 | Moderate longer waves. Many white horses, some spray | Small trees sway | Hard effort and paddle flutter. Cross winds awkward. |

As a rough guideline, wind of force 1-2 doesn’t affect kayakers too much. It makes sense to plan to paddle upwind at the start of the day when the wind is force 2-3, and certainly when it’s stronger than that. For inexperienced paddlers, boat handling can become tricky in force 3-4 winds, and less strong paddlers may find it hard to paddle upwind.

A few subtitles about interaction of wind with land and water:

When wind, or waves are going the opposite direction to a tidal stream, they become shorter, taller and often break - we call this ‘wind against tide’

If the wind is strong, it often makes sense to seek coastlines that are sheltered from the wind. However, the wind on these coastlines will blow offshore, creating a potential hazard. What seems like a light wind close to land and cliffs may be a strong wind further out. If the group gets blown away from land, getting back to shore may be difficult.

We can sometimes gain protection from the wind by tucking in close to the coast - e.g. into bays and behind headlands. This does, of course, depend on the way the wind is blowing, the shape of the coast and how tall the cliffs are (this tactic tends to be ineffective on the East Anglian coast!).

The wind blowing over the sea creates waves. The further and harder it blows, the bigger the waves. When the wind stops blowing, waves continue to travel across the ocean as a swell.

Waves reflect off cliffs, sometimes at an angle. The reflected waves interfere with the incident waves to create a steep, and often confused sea close to cliffs.

3.3 Swell forecasts

Wave and swell forecasts can be obtained from most of the same places as wind/weather forecasts. It’s sometimes also worth consulting information intended for surfers - e.g. http://magicseaweed.com. Wave forecasts will normally include:

- Wave height - can our group cope with the forecast waves? What effect will they have when they strike the coast? Waves of 1 meter will feel serious to an inexperienced group. This is about the height when group members will sometimes disappear in the troughs.

- Wave period - long period swell (e.g. 10 seconds or greater) is easier to paddle in than short period chop. However, long period swell implies a bigger wave for a given height, so the effect of the wave breaking will be more powerful.

- Wave direction - suggests where we can find shelter. Waves will tend to diffract around headlands, so shelter may be imperfect depending on the shape of the coastline. This video (15 mins) gives a good illustration of this sheltering effect. If you watch it, I suggest keeping a map of the area to hand so that you can easily understand how the locations mentions relate to each other.

3.4 High and low water

3.4.1 Using tide tables

Tides are caused by the moon pulling on the water in the earth’s oceans. Around the UK, the tide varies from it’s highest (high water) to it’s lowest (low water) over about 6 hours. The range of the tide varies by location and over time. The largest tides are called ‘spring tides’, the smallest ‘neap tides’. It takes about a week for the tide to cycle from springs to neaps.

The tide at ports is of significant interest to mariners and data exists on the height of tide going back many years. For example, data at https://www.bodc.ac.uk gives records of the tide at Newlyn in Cornwall going back to 1915. These data enables very accurate forecasts to be made of the times of high and low water at locations known as ‘standard ports’, which are given in tide tables.

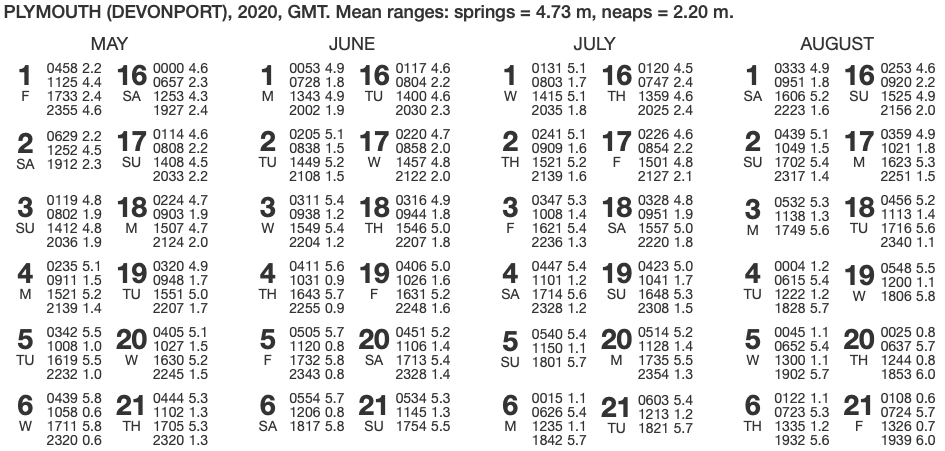

Tide tables are easy to use, but often report times in Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). During summer, when British Summer Time (BST) is in operation, an hour needs to be added to give the correct time. Some tide tables are given with the corrections for BST already applied - so always check if you’re using an unfamiliar tide table!

Tide tables are available from many sources. I find that the most useful are:

- The National Tide and Sea Level Facility: Accurate data for all major UK ports for the next 28 days.

- Easytide: UKHO site giving predictions 7 days ahead for practically anywhere in the world.

- Visit My Harbour: An impressive array of free tide tables for the whole of the current year.

- Imray Tides Planner phone app - provides yearly data for a few pounds

Tide tables can, of course, be purchased in printed form. They also appear in nautical almanacs that are republished each year. I find it useful to obtain a copy of Reeds Small Craft Almanac each year so that I’m not reliant on an internet connection when I’m doing tidal planning.

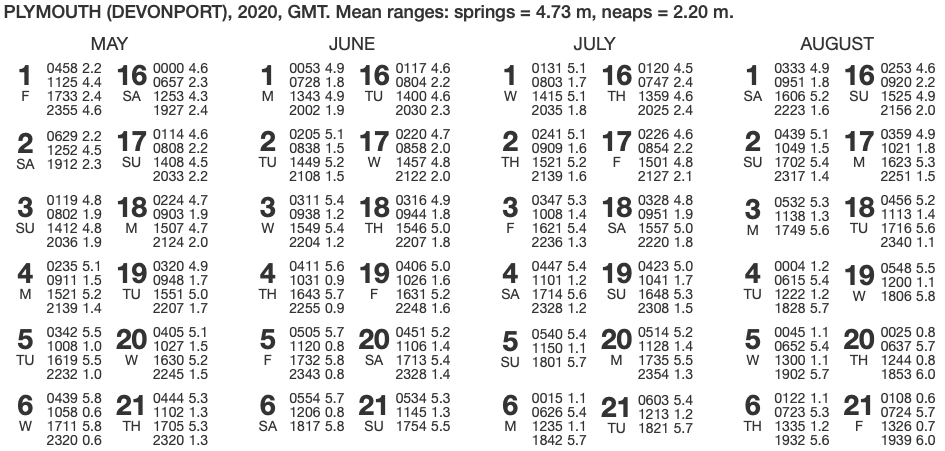

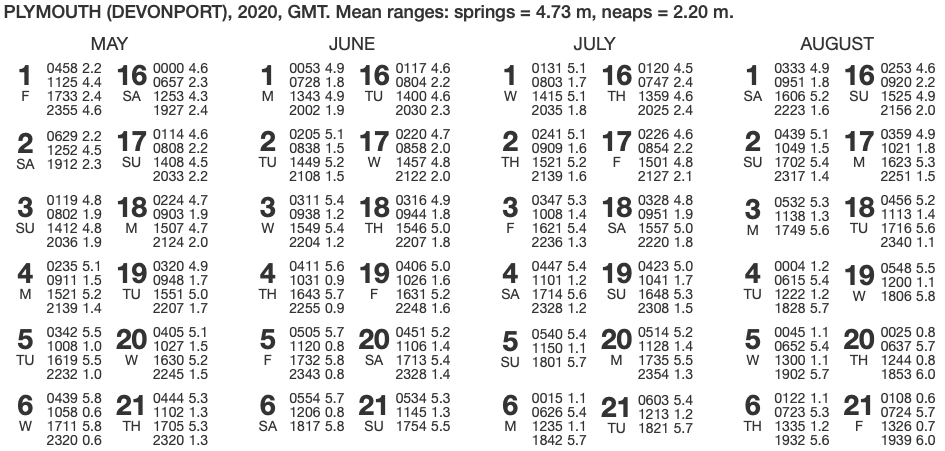

Find times of high and low water during the day at Plymouth on June 4th 2020.

Consult the tide table for Plymouth above. Note that times are given in GMT. Find the entry for June 4.

Big values of tidal height (5.6 m, 5.7 m) must refer to high water (HW). Low values (0.9, 0.9) refer to low water. So, during the day, the times are:

10:31 GMT 0.9 m Low water

16:43 GMT 5.7 m High water(we’re ignoring the early morning high tide and the late night low tide)

Being June, British Summer Time (BST) is in operation. To convert to BST, we must add one hour to the times given:

11:31 BST 0.9 m Low water

17:43 BST 5.7 m High water3.4.2 Find local high and low water times

We saw in the last section how to use a tide table.

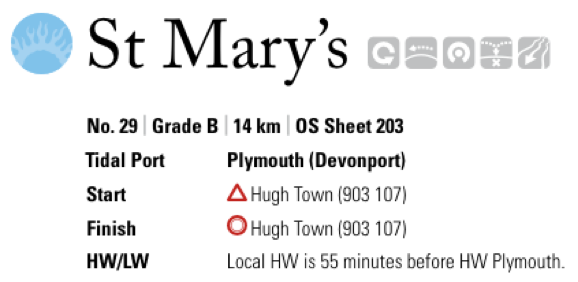

Such detailed data is not available everywhere that we would wish to paddle. To overcome this problem, reference books quote tidal constants for other locations. These are either added or subtracted to times of high and low water at standard ports to give local high and low water times. For example, this extract from a paddling guidebook tells us when HW and LW will occur at a location in the Isles of Scilly.

Find times of high and low water at St. Mary’s during the day on June 1st 2020.

Using the tide table, we can find the times of high and low water at Plymouth - ignoring the high water in early morning, and the low water late at night and remembering to add an hour for British Summer Time:

08:28 BST High water Plymouth

14:43 BST Low water PlymouthWe are told that HW and LW occur 55 minutes earlier than they do at Plymouth. Subtracting 55 minutes from the Plymouth times gives:

07:33 BST HW ST MARYS

13:48 BST LW ST MARYS3.4.3 Effects of tides on planning

The degree to which the rise and fall of the tide affect our paddling plans depends on where we’re going paddling. Where coastlines are steep cliffs and the water is deep, the effect may be small. When coastlines are less steep and the water is shallow, large areas of the sea bed can be exposed at low water. This can make for long carries across beaches to get to the water. In some cases (e.g. paddling in estuaries), the options we have to paddle may be very different at high water and low water. The best approach to this is to consult a nautical chart - areas that dry at low tide are shown in green.

Often, we find that tidal streams, flows of water caused by the tide, are equally important for paddlers to consider as times of high and low water.

3.5 Tidal streams

The Sea Kayak Award is limited in scope to areas where tidal flow does not exceed 1 knot, and tidal planning is not explicitly covered in the syllabus. However, it is important to be able to identify locations where there may be strong tides, and it may well be important for our planning on the course trips to understand tidal streams.

A range of information sources about tidal streams exist, but we will focus here on using sea kayak guidebooks (like the excellent ones produced by Pesda Press).

Sea kayaking guidebooks include the most important tidal information from pilots and other sources. Being focused on kayaks, rather than large ships or yachts, they’re a great source of information in a compact format. Over the last few years, Pesda Press has published an excellent set of guidebooks covering most of the UK.

Guidebook information is presented in a fairly understandable format. Its use is best illustrated by an example.

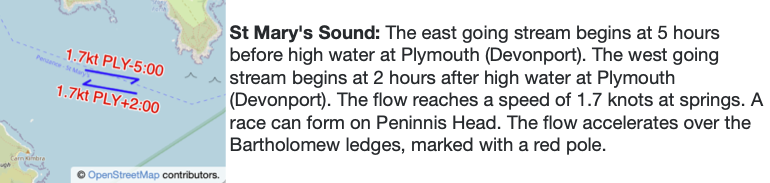

Describe the tidal flow in Saint Mary’s Sound on June 1st 2017

We begin by consulting a tide table to find high water times for Plymouth, being careful to account for British Summer time:

We’ll focus on the afternoon high water at 14:43 BST. We’ll need to subtract and add times to this as described in our guidebook extract above:

The ESE stream begins HW Plymouth -5:00

14:43 – 05:00 = 09:43 BST

The WNW stream begins HW Plymouth +2:00

14:43 + 02:00 = 16:43 BSTSo, we expect the tide to run ESE from 09:43. It’ll turn WNW at 16:43.

3.6 Access and escape options

Whilst it’s possible to guess at places we can access the sea by looking at a map, and (sometimes) to check on feasibility with Google Earth, its far easier to consult information in guidebooks.

Difficultly of using a given access point might depend on:

Whether we can park cars nearby

How busy the location is - often depends on time of the day and of the year

How far we’ll need to carry boats from the car to the sea (may depend on how high the tide is)

Whether it’s an easy carry, or a route with steps, corners, slippery rocks etc.

Will we be launching off a beach, a slipway, a pontoon or a harbor wall?

Do we expect waves and surf at our access point?

Is there a sheltered area close to the access point to warm up?

We should always have fallback plans in place in case we can’t make it back to our chosen access point. Clearly, we might accept less ideal options for these fallback plans, but we do need to be sure that the escape routes we choose are usable (e.g. not likely to be impossible due to heavy surf). In some locations, e.g. those with tall cliffs, it can be difficult to egress from the sea along long sections of coastline.

3.7 Synthesizing information

It’s fairly easy to learn to understand a weather forecast, predict tides and get information from a guidebook. The real challenge lies in synthesizing this information to create a good plan for a day’s paddling - especially when conditions aren’t straightforward.

The ability to make good plans comes with time and experience. However, the following process might provide a guide for beginners:

A) Choosing where to go

Check wind strength and wave size. Is the wind light enough (e.g. F1) that we can ignore it? Is it strong enough (e.g. F4 or more) that we need to hide from it behind land? If not, it’s probably still sensible to plan a paddle that starts upwind, so that the wind is behind us at the end of the day.

Assuming we need to consider wind, use an overview map of the area to identify coastlines that we might be able to paddle on and access points that allow us to start upwind. This should give us a short-list of options

Are there any tidal effects (height of tide, tidal streams) to worry about for the areas in our short list. Does this limit options due to (e.g.) wind-against-tide effects, having to paddle against tidal stream or access constraints due to areas drying out?

Are there any other limits to our options or hazards to consider - e.g. other water users, danger areas, logistics, lack of escape routes?

We should now have a list of options that are safe and practical, and need to discuss which we’d prefer to do.

B) Focused planning

Confirm wind, waves and tide for the area. How will they change through the day? How do we expect the shape of the coastline to affect these? Do we need to consider other factors (e.g. shipping, local rules…)?

Where are the put ins and take outs? Where do we park and how far do we need to carry? Where else can we get off if things go wrong?

How far will we paddle? What are the rough timings? Do they fit with weather and tidal changes? Are there critical places that be need to be at specific times? Where will we stop for breaks and lunch?

What are the main hazards and where are the crux points of the trip (e.g. exposed sections, headlands, concentrated wind, waves or tidal stream?). Where are our key decision points to keep going or turn back? How will we make those decisions? Do we have fallback plans if conditions prove worse than expected? At what points do we become committed? What will we do if things go wrong at each point?

Finish by copying key information to the map that you will carry on the water. Aim to keep your plans flexible - consider different options and be prepared to change if things don’t turn out as expected.